Chris Andrews

Notes and Overview for Week 7

A diatribe on professional language and the 7Cs

The 7Cs of communication are principles for “good technical and professional writing.” They have come up in our readings a few times, but I haven’t done much editorializing about them yet. This short article overviews some of the complications related to navigating the 7Cs as a real, live, human being.

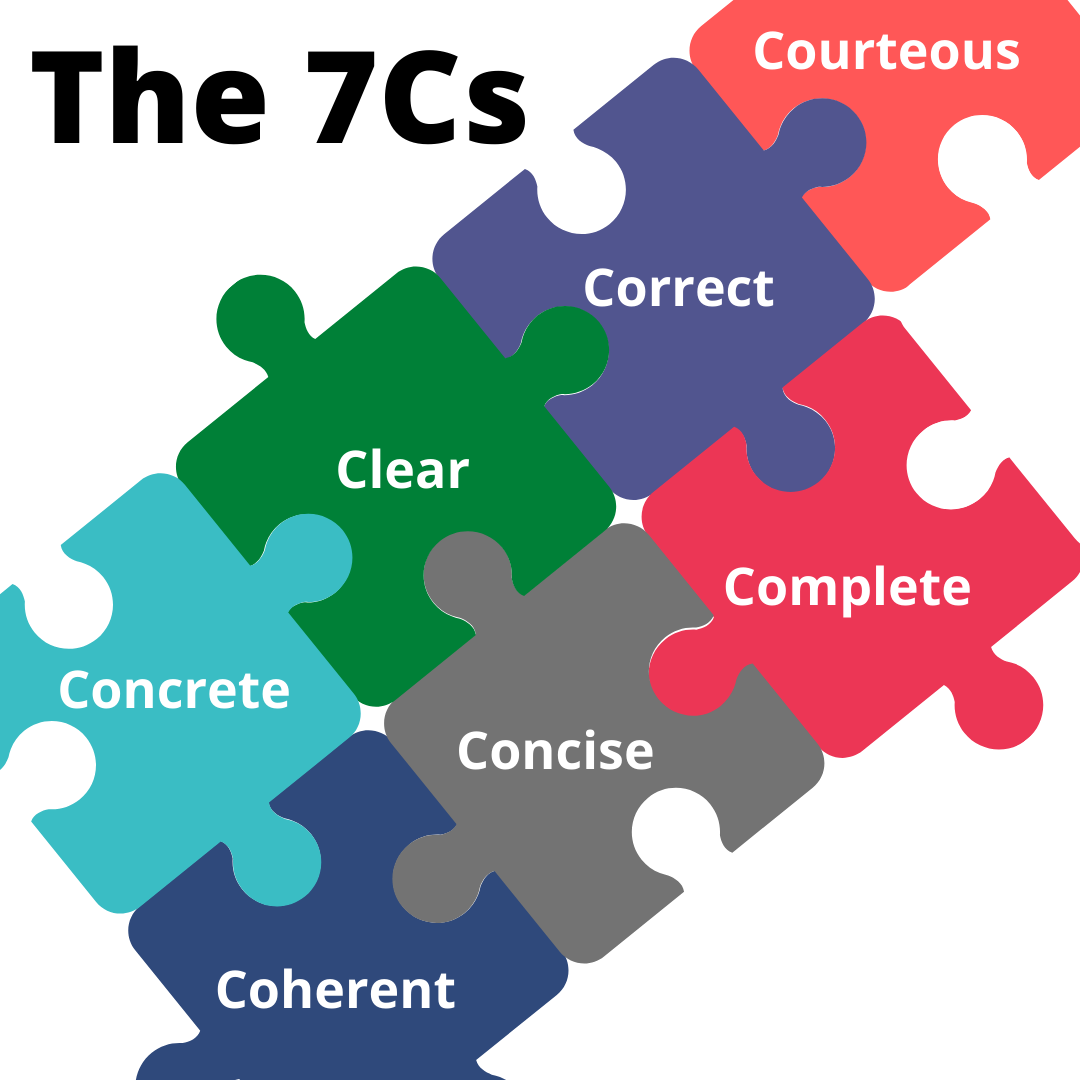

The 7Cs are a useful short checklist of qualities effective communication ought to have. Good technical writing is:

These abstract qualities are like variables in a multivariable communication equation that as writers we need to account for. Generally they are thought of as things that can help reduce the “noise” in our communication–that is, being clear, concise, coherent, and so forth can reduce the potential for miscommunication. Some of them might seem to be in direct conflict with each other sometimes (it is hard to balance complete with concise; other times being concise might get in the way of being courteous). The conflict inherent in these qualities is one of the toughest things for us as new technical and professional communicators.

The 7Cs aren’t abstract norms that we can somehow attain with prayer and meditation. “Clear” is a judgment of an audience with expectations and knowledge (or lack thereof). “Courteous” to your mother and “courteous” to your BFF and “courteous” to an interviewer the first time you meet them for a job interview are very different in reality, right?

On top of that, the 7Cs are, historically, a langauge standard that has been used to exclude, deprive, and harm people who don’t use language in a few normalized sanctioned ways. Often you hear folks talk about “Standard English.” That’s code for the English that gets taught in schools, printed in newspapers, and spoken by news broadcasters in most parts of America. But there’s no real “Standard” for English. In fact, even the idea of a “standard” English is a kind of linguistic discrimination. If you don’t speak the standard, then you’re at an automatic disadvantage. Language discrimination has historically been used to keep Black, Hispanic, Asian, Indigenous, and other groups disadvantaged and disempowered, whether through the creation of texts that they’re not able to read because it’s not in their language, through the oppression of their own dialects and languages through schooling, through the diminution of these communities’ voices and stories in society, or through negative constructions of those groups created and perpetuated by discourse.

This is definitely territory we have to deal with in professional and technical writing, as “Standard English” has a long history in performing a gatekeeping function in the American economy. You want a job? Write white. You can’t? You’re out, tough. That’s not an ethical or just position, in my book. People have a right to they own English.

We should on the on the side of people, ethics, justice. That doesn’t mean ditching the 7Cs entirely, though. It means putting them in proper perspective, and remembering that (just like rhetoric) they are contextual, embodied, and shifting. Language is always shifting, and language is always connected to race and power. (We’ll talk more about that in the weeks to come.) Technical and professional communicators must use the language practices of actual people and embrace varied languaging. “Clarity” can’t be a standard. “Is it clear to me?” and “Is it clear to you?” on the other hand? We can work at that.

The 7Cs are a balancing act.

Sometimes to be clear you need to sacrifice concision. Sometimes to be courteous you need to sacrifice correctness. Sometimes to do one of the Cs, you have to back off of one of the others.

You-attitude is an excellent example of the balance between the 7Cs. In tech writing it is often useful to use the second person pronoun (“you”); doing so tends to structure sentences around a simple, active subject and verb. (You should…. You will… etc.) If you’re giving instructions or corresponding with an audience, “you” is powerful and you’ll see it used that way frequently. Especially if you’re giving good news or neutral news, the second-person POV can be clear, courteous, and concise. On the flipside, if the news is bad (“You’re doing a terrible job. You’re fired.”), the concise, you-centered version is downright hurtful. In bad-news situations, you’d need to add some contextual information, redirect a bit, and provide positive-looking alternatives.

One strategy for staying person-centered and balancing you/they/it perspectives: if you don’t want to use “you,” use a general class noun for the subject instead. Instead of “You should edit your work if you want to get an A in the class”, you could write “Students should edit their work if they want to get A’s in the class.”

A professional style does vary from one work community or profession to another. In some organizations (imagine a startup company for a new social media app) a certain amount of casualness is acceptable, while in other firms (imagine you’re a content manager and editor for an international dictionary company) a more formal approach is called for. In Engineering, writers almost always use the passive voice to describe methods in an experiment, while in many humanities disciplines it’s considered more ethical and clear to use active voice. These differences can be relational—the first time you correspond with someone at work, it might be a little on the stiff side, but as you get to know each other, things might become more casual. And these differences can be cultural, as well. In Japan, starting a letter or email with the “bottom-line-up-front” is considered RUDE; instead, communication in that culture often begins by inquiring about the health of the reader’s family or asking about a recent vacation or other social matters. In American business culture, most readers want to skip the niceties and get right to the business at hand; oversharing about your aunt’s open heart surgery last week is inappropriate and rude. But even then, it can go too far; we’re still people, and one way to push back against organizational cultures that chew people up and spit them out is to write like humans to humans. Tech writing is for people!

The complex, variable, and even negotiable nature of style guidelines is why doing a little research about audience and taking time to learn about the kinds of audiences you’ll usually write for is a valuable step. Audience analysis is a research and planning activity that can help you get a more specific idea about who you’re writing to. Then, when you’ve got an idea about your audience, you can make decisions about about how much detail, what register of language, or what type of “courtesy” you need to typify your writing.

Questions to help you analyze your audience:

- Who is the intended reader? A coworker? An executive? A customer? A prospective buyer? Your boss? Your subordinate? Notice that navigating audience is about navigating relationships. (Some of us may be thinking “oh, relationships? I got this!” Others of us might be freaking out at he thought of relationships.)

- Why are they reading the document? That is, what are they going to DO with it?

- What are their needs and values relevant to the situation? (Do they have a particular task to complete? Do they need to make a specific decision? Do they have attitudes or values that might impact their decision-making or understanding of your communication?)

- What is their age, educational background, gender? Are there cultural communication differences to account for? Are they a college graduate, or do they hold an advanced degree? Are they educated in the same field as me or different? high school? even lower-education level or maybe have a cognitive disability?)

- What is their interest level? Do they have to read it or do they want to read it?

- What will the audience expect or expect to learn from the document?

- How much do they know about my subject? A lot, or a little? Are they technical or nontechnical?

- Are they up the orgnaizational heirarchy or down it from me? Do they have more institutional power than you or less?

Another strategy for figuring out if you’re balancing the 7Cs is testing your writing before you send it out—a standard form of collaboration in most workplaces is: “Hey, will you read this before I send it out; do I sound too mean? Or not mean enough?” Getting a test reader to give you some feedback can help you figure out when you’re talking down or when your vocabulary is too complex.