My observations on your codecademy reflections.

Or: Into a looking glass, div-ly.

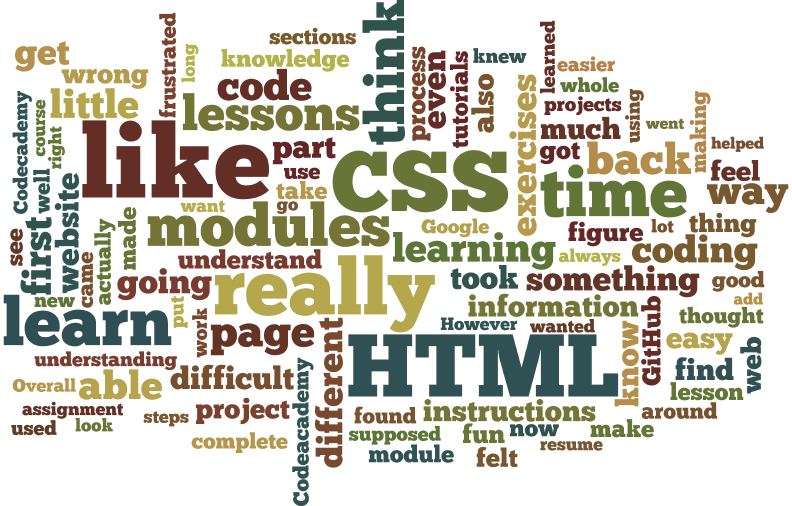

I made the above word cloud with a tool called wordle (www.wordle.net--it will probably work best in Firefox). There are other word cloud and text analysis tools that are more powerful (try Voyant), but I just wanted to put together a quick frequency visualization of the top 100 words in your reflections. These are from all of the reflections I've received as of Feb 21. If you've never used a word cloud before, they display the most frequently used words in a corpus (after taking out common words like it and the). The more times it appears, the bigger the word.

The biggest ones in this figure should be no surprise: HTML and CSS. I think there are some other interesting ones in the top 100: like, really, learn, and time jump out to me, as do able, instructions, and back. (Oh, back!) When you look at the word cloud, what do you see?

I am pleased with your work on this project. My goals with the Codecademy project were to get you to look under the hood and think about web writing from a technological angle rather than just a style/content angle. After reading your reflections, I feel like we got there.

While the literacies you need for composing a school paper, a letter, an email, a text or tweet are readily available to you and part of your regular writing habitus, this process reminds or make present to us the technological literacies necessary for working with web writing: the process of uploading and maintaining files, of being detail-oriented in an entirely different realm, or the mechanics of linking files to files and pages to pages. The seemingly simple, taken-for-granted process of styling a text in Microsoft Word is rendered complex and frustrating (at first) in a new markup language. Some writers have touted the Internet as the great democratizer, making information and publication easy and available to all people; after doing a bit of tinkering with your modules, I hope you can see why that statement is at the same time true and limited.

The rest of this document will comment on some of the dominant themes (in no particular order) that arose from your reflections. Click on the section headings to view comments for each.

Normal college student stuff

A collection of issues you commented on were what we might consider classic student issues. I've been teaching for over a decade, so I can expect that making allowances for time, note-taking, and reading instructions are going to be a problem. Many of you commented that you were surprised at how much time these took to start, but eventually things seemed to pick up as the projects got more interesting and you became more confident in your growing skills. Likewise, note-taking. While some weren't sure how to take notes, others clearly connected jotting down a few notes about selectors, tags, and nesting with success in later modules. Don't overlook the process of scratching things down on a piece of paper! Finally, a few of you noted that if you'd read the instructions more carefully, things would've been smoother. I wish that all things could be intuitive and easy to just pick up and fiddle with, like a rubix cube. As a professor of technical communication, I know that good instructions are hard to write--and if you noted a problem or issue or straight-up error in my instructions, please let me know!!

Details, details, details

When I was an undergraduate, my professor of 18th century English Literature, Dr. Miller, had a favorite saying that she engraved into my memories: Good writing is attention to detail. The best writers aren't the most creative, most florid, most passionate people. They're the ones with the most attention to detail. For a lot of you, HTML and CSS tested your attention to detail. All of our communication is encoded (dig into communication theory a bit), but for those of you who've been writing fluently in English words and sentences for a while probably haven't had to pay attention to that code as code. HTML, to work, to be understood by machines and humans on either end, has to be *right*, just as in English, you can't say "lady red hat is" and expect to be understood. Details are wonderful things. Attend to them!

When in doubt, Google it!

A couple of folks commented on or asked about the sheer amount of things you had to remember to make a simple HTML page. Part of that comes with repetitions--just like you learn new vocabulary words and punctuation marks and sentence structures. But in all seriousness, there's a LOT to remember in this markup language, lots of it you don't use every day, and worst of all, sometimes it changes! That's why for web developers and writers, having some kind of code references or cheat sheets are a normal thing. You can find good ones online. I like to use The Mega Cheat Sheet. Also, that funky layout you're trying to do but haven't figured out yet? Someone has found a creative solution to that problem and a million others, and they posted it online. It's not cheating to use that stuff in this kind of work, and you can usually find good ones at places like stackoverflow. I'll be 100% honest. I may be able to do the "box model" in my sleep, but I feel like I have to re-learn CSS positioning Every Single Time I work on a website. So I look up positioning references and use other people's solutions when needed.

I got 99 problems and Codecademy is one...

A few of your issues were problems that had to do with the nature of the modules: sometimes Codecademy didn't always explain why, instead being mostly focused on the what. Sometimes it didn't define terms all that clearly. That is a limitation of the modules, but one that you can work around by asking questions early and often.

...but GitHub was the other 98

GitHub Frustrations were nearly universal. I'll be honest: Your group are guinea pigs this semester; I've not used GitHub in a class this way before, and will decide whether or not to continue using it in the future based on your feedback. If the reflections are any indication, the process was confusing and unnecessarily complex despite best walkthrough intentions.

HTML can be hard

As I was reading through your reflections, many of you pointed out one way or another that HTML--or at least some aspect of it--is hard. The major culprits:

- Tables. I agree. HTML tables are noxious and evil and bad and I hates them. Once upon a time (I shudder to remember) we HAD to learn tables to do grid layouts in HTML. Thankfully, those dark ages are gone. Save tables for tabular data. Lots of web writers cheat and use images (not very accessible) or add-ins (you can have a program "code" your table for you. Magic.)

- Nesting. Yes. Until you get the hang of it, nesting can throw you for a loop--especially remembering which tags nest with others, which ones don't, and which ones are self-closing. This can get hard to follow in longer web pages: I"ll show you a few, but we won't get into that kind of webbing in this class, most likely.

- The document head section. Thankfully, HTML5 made declaring the doctype really easy, but contents are still tricky. This is part of the "why" not just "how" stuff that codecademy doesn't explain very well since it's not a visual aspect of the page. Suffice to say that this section is about metadata (information about information) and linking to other needed files (stylesheets, javascripts, font stylesheets, and the like).

- Details matter, Redux. As I noted before, a mislaid space, /, < , or > can be the difference between something working and something looking like poomoji. And we didn't even get into character entities like & which have their own special code (do a right-click and view source, and you'll see it). That's where working in code generators that color-code and sometimes even automatically verify your document can be very helpful. They'll "spell-check" your document for those kinds of errors. Brackets is one tool that's particularly good at this, in my experience.

- Finally, in HTML some things just can't be done easily. Horizontal alignment--getting text aligned on a page--is cake. textalign: center. Boom. Done. Vertical alignment, on the other hand, is eighty times more difficult because there are so many variables involved in "centering" something that doesn't have a bottom boundary. When in doubt, google it. You might just find out that it's impossible and you don't have to bang your head against the monitor any more!

Finally, the list of most common yay fun things you wrote about:

Seeing my cool (often pink) project come to life, and being able to personalize! A great many of you commented that you liked working on your simplified resume and making those practical, personal changes. Also, underwater puppy pictures.

Nearly everyone described how good it felt to progress, to recognize that you were building knowledge on prior knowledge to make something. Strongly related to this was your sense of joy at overcoming difficulty. There's not too little I could say about the refreshing power of accomplishment and self-reliance with appropriately-difficult learning situations.

Finally, a number of you noted that this was entirely new and fascinating. The modules opened up a new world that you could experiment and tinker with. Even if we don't ever become HTML masters, we can see ourselves learning the next cool CSS trick, and the next, and the next